David Halpern, founder of the world’s first behavioural insights unit, says it’s more important than ever that policymakers understand human behaviour

Back in the early days of Tony Blair’s newly created Strategy Unit, I invited Danny Kahneman to join us for a private discussion about his work. Danny was well known to psychologists, and had an increasing following among economists, but he was not well known in the policy world. He had yet to win his Nobel Prize.

We talked about the policy implications of his work. Danny highlighted a seemingly paradoxical paper by economist Richard Thaler on ‘libertarian paternalism’ – later wisely popularised as ‘nudging’. The importance of Thaler’s work was immediately obvious: economics upgraded with a realistic model of humans at its centre.

Since then, figures such as Kahneman and Thaler have become household names. Most policymakers know that the challenges they face, not least the new Government’s five missions, almost always need to take account of human behaviour. Sentiment affects growth, for example. (Bad) lifestyle choices explain the majority of ‘lost’ years in an otherwise healthy human being. And if the green revolution is to succeed, we must all get used to driving EVs and installing heat pumps.

Despite all this, the ‘human’ at the heart of policy and practice is too often only thinly understood.

A bumpy road

Viewed through a classical economic framework of perfect information and ‘rational’ agents, it shouldn’t matter whether people have to opt in or opt out of a workplace pension scheme. But as Thaler’s work explained, the tiny reduction of friction and hassle that comes from making people opt out – rather than relying on them to opt in – makes a huge difference. After reading his 2002 paper, I sent a hard copy to Adair Turner who was leading our pensions review, with a scribbled note on No.10 notepaper saying: “probably the most important paper you will read!”

The timing was not auspicious; around that time the Prime Minister’s Strategy Unit published the paper: Personal Responsibility and Changing Behaviour: the state of knowledge and its implications for public policy. It caused an unexpected and negative media storm with The Times running a leaked extract on its front page stating “Downing Street declares war on obesity”, and the BBC pronouncing that “Government Unit urges fat tax”.

Leaving aside the question of whether the UK would today be a thinner, healthier nation had that particular policy been pursued, the experience seared into the then No.10 that behaviour change – particularly anything that might be interpreted as the ‘nanny state’ – was a dangerous game. Yet behaviourally-inspired ideas, such as auto-enrollment in pensions, looked like powerful and important policy tools.

Fast forward a decade, and both Barack Obama and David Cameron had overtly embraced the idea of behavioural science – and ‘nudging’ in particular. On both sides of the Atlantic, behavioural approaches started to be seen as an alternative to an ever-expanding and legislating state. President Obama was keen to stress that the key challenges in society could not be fixed by governments – or regulation – alone. For example, in a speech on education in 2011 he declared that “…schools can’t do it alone. As parents, the task begins at home. It begins by turning off the TV and helping with homework, and encouraging a love of learning from the very start of our children’s lives.”

In the UK, the newly-minted Behavioural Insights Team (BIT) worked alongside a drive to deregulate and create a ‘Big Society’ within which government could support citizens to “make better decisions for themselves”. While the politics of Big Society stumbled, the application of behavioural science scored significant wins. Adding an extra line to HMRC letters to late taxpayers that “most people in your area pay their tax on time, and you are one of the few yet to do so” led to a 16% increase in payment without further prompts relative to controls. Prompting jobseekers to think about what they would do next week to get a job, rather than checking on what they did last week, got them back to work 10% faster.

At the same time, the Turner proposals from a decade before were finally coming to fruition. Exactly in line with prediction, shifting from an ‘opt in’ to an ‘opt out’ model was spectacularly successful. Among eligible workers, 9 in 10 stuck with the default, and within a few years, more than 10 million extra UK workers were saving. A simple nudge had achieved what hundreds of billions of pounds in tax subsidies had failed to do.

So where are we now?

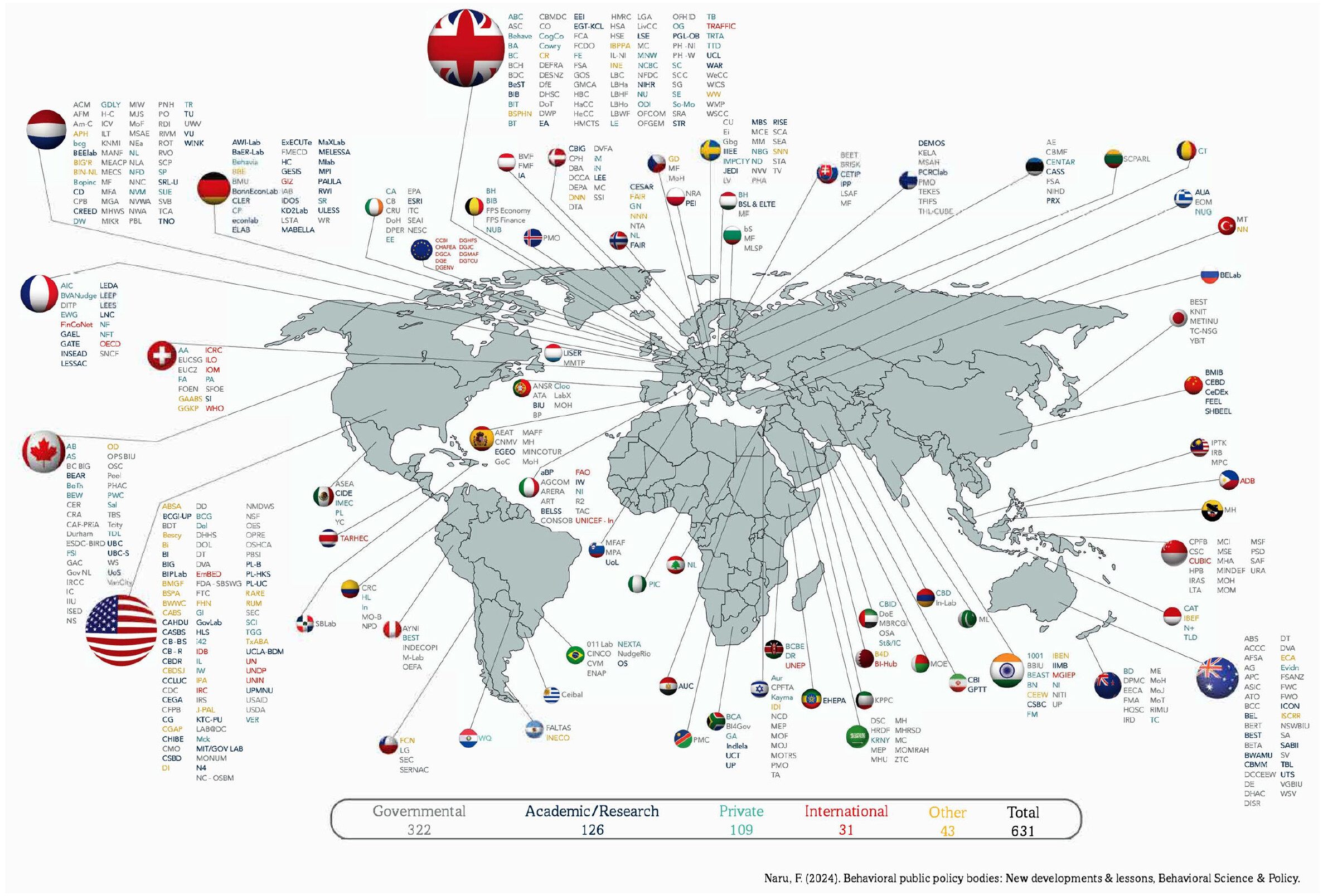

In the wake of the successes, many departments and other governments set up their own behavioural teams, often supported by the UK’s BIT. A recent mapping identified over 600 behavioural public policy bodies worldwide, with just over half being within-government units [see figure, courtesy of Faisal Naru, formerly Senior Economic Advisor in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)]. A meta-analysis of ‘simple’ comms nudges by the White House and BIT’s US team found that the average effect of all their interventions was an 8% improvement – impressive given the low cost of such actions.

Behavioural interventions have spread well beyond getting people to pay their tax on time, or back to work faster. They have been deployed to encourage the reintegration of ex-combatants in war zones; increase diversity in workforces; reduce traffic accidents; reduce over-prescription of antibiotics; save tigers; reduce intimate partner violence; and increase vaccination rates, including through the use of behaviourally-informed chatbots. There have also been big successes with ‘upstream’ interventions, such as the UK’s added-sugar levy, which led to a halving of sugar in UK drinks, while the 2021 recommendations for a wider set of taxes by the restauranteur Henry Dimbleby – ruled out by the last Government – are reportedly back on the table.

Covid-19 further raised the profile of behavioural insights. Rapid testing of public health messages, for example, improved comprehension and intention to comply. Better compliance with requests to test and isolate followed the introduction of behaviourally-informed adaptations of follow-up calls. The uptake of vaccines was enhanced, including through segmentation of those who had yet to have vaccinations. This showed that the majority were not ‘anti-vaccers’ but were ‘intenders’ – people who intended to get vaccinated but just hadn’t got around to it. For these people, the most important thing was to make it easy for them through initiatives like mobile vaccinations and extended hours – and certainly not campaigns to punish or vilify them.

Behavioural basics for policymakers During its formative years in the Cabinet Office, the Behavioural Insights Team developed a simple framework for policymakers seeking to affect behaviour: “Easy, Attractive, Social, and Timely” (EAST). It is still a pretty good starting point.

In addition to the basics of ‘EAST’, policymakers might also:

|

The secret sauce: experiment!

One of the biggest impacts of behavioural science in government has been the growth of experimentation in policy and practice. With the support of Cabinet Secretary Jeremy Heywood, BIT pushed a ‘test-learn-adapt’ approach, including randomised control trials (RCTs), quasi-experimental designs, and machine-learning models. It was quite a moment when the full Cabinet thumped on the table in celebration of the results of those RCTs.

This empirical approach was extended further through the creation of the ‘What Works Centres’. For example, the Educational Endowment Foundation went on to run over 200 large-scale RCTs with more than 2 million children, becoming the world’s largest producer of high-quality evidence for what works in schools, and widely admired by other governments.

The US and other governments recalibrated their approach on the back of these UK successes, and the use of robust experimental approaches. They also prepared the way for important institutional developments such as the CO-HMT Trial Advisory Panel and later Evaluation Task Force. Most recently, the test-and-learn approach has been championed by Cabinet Office Minister Pat McFadden, placing it at the heart of ‘how’ missions can be delivered.

Challenges

There is now a much wider understanding of how most policy challenges concern human behaviour. Nonetheless, there are challenges. There has been a tendency to conflate ‘behavioural’ with communications-based interventions, such as rewording letters or prompts. This has led to what Richard Thaler, now a Nobel Laureate himself, has called “permission bias”: only being given permission to make small or limited tweaks, while bigger changes to the ‘choice architecture’ are ruled out (such as auto-enrollment).

To illustrate, BIT was commissioned in Australia to test alternative messages that might get people to reduce electricity use at peak times – but it was initially barred from sending these messages without the customer opting in beforehand. The results? We found little impact from varying the wording of invitations for customers to receive these texts. However, when allowed to test the impact of sending these texts at peak energy use times by default (albeit, allowing them to opt out), we found large reductions in peak energy use. Too many policy briefs limit interventions to tweaking language; more radical options are excluded before the work has even begun.

Behavioural science has yet to have its full impact in many areas. For example, behavioural economics has had a surprisingly modest effect on economic policy, including on the UK Government’s priority concerns of growth and living standards. Economic policy remains the bastion of the ‘efficient market hypothesis’, built on rational ‘econs’ and perfect information.

Introducing behavioural economics makes life messier, but opens up a variety of promising levers. ‘Mental accounting’ (how people categorise and evaluate their finances) makes sense of why winter fuel allowances and apprenticeship levies aren’t just ‘anomalies’: people put different types of spending in different mental boxes, limiting the classically presumed ‘fungibility’ of money. Addressing the mental strain of debt cycles with rainy day savings may offer a far more effective boost to growth and living standards than huge tax subsidies for pensions. Social trust – trusting other people – explains more variance in national growth rates than human capital (education), yet does not feature in our economic policy. Perhaps most glaring of all, addressing the frictions and ‘shrouding’ in markets (irrelevant to econs but a huge issue to humans) offers a powerful lever to boost growth, including up to an estimated doubling of productivity growth.

Applying the lessons to mission-led government

The pragmatic successes of behavioural science, and the experimental methods it has popularised, have clear implications for mission-led government. Missions set a high-level objective, but are open about the means to delivery. Missions invite experimentation.

Behavioural science also reminds us that policymakers and practitioners are humans too, pulling back the curtain on our own biases and preconceptions that lead to missteps (see box). Even the best and brightest are prone to overconfidence, fixation and seeking confirming evidence (rather than looking for counterfactuals). Policymakers are as prone as anyone to the ‘illusion of explanatory depth’: thinking that because something is familiar we therefore understand it, and know what will work. Using the lens of behavioural science on ourselves and our institutions brings new tools into focus.

Contemporary behavioural insights are also converging with AI, from the human biases that are inadvertently ported into AI models, to the human factors that shape how we interact with our new ‘silicon’ partners.

Most of all, behavioural science brings a vital humility and grounding to the heart of policy, and one that we need to hard-wire into how we do government. It gives us new insights and ideas, including understanding ourselves, the markets and our fellow citizens. It alloys these insights with the rigour to ask, maybe this great idea won’t work; maybe people won’t respond the way we think; why don’t we test it? Effective contemporary government demands the combination of daring, humility and the use of robust empirical methods.

Now that’s something to get excited about.

David Halpern is President Emeritus of the Behavioural Insights Team (BIT), an independent global research and innovation consultancy with 220 staff and offices in seven countries.

The author (left) and Richard Thaler together outside No.10 Downing Street, circa 2015 (with Larry the cat). Both were back in No.9 in November 2024 for a joint seminar on behavioural economics for the new Government.