Suzanne Heywood on the qualities valued by her late husband Jeremy, Cabinet Secretary from 2012 to 2018.

In late August 2018, Jeremy, Jonny (our eldest son) and I drove down to Whitstable for a long weekend. It was to be our last holiday together – something we suspected at the time but were far from acknowledging. By then I had almost completed the first draft of Jeremy’s biography (“What Does Jeremy Think?”) – a book that was the product of countless hours of conversation between us – but there was something I felt we hadn’t discussed: what, in Jeremy’s view, made a great civil servant?

This became the topic as we wove our way through traffic on the M2. I recorded the conversation on my mobile, but I have never shared the contents of it, until now. The first edition of the Heywood Quarterly seemed like the right place to do so. After all, Jeremy championed the creation of its predecessor, the Civil Service Quarterly, becoming its first editor – and it would have delighted him to know a new publication with the same, perhaps even loftier, aims honours his name.

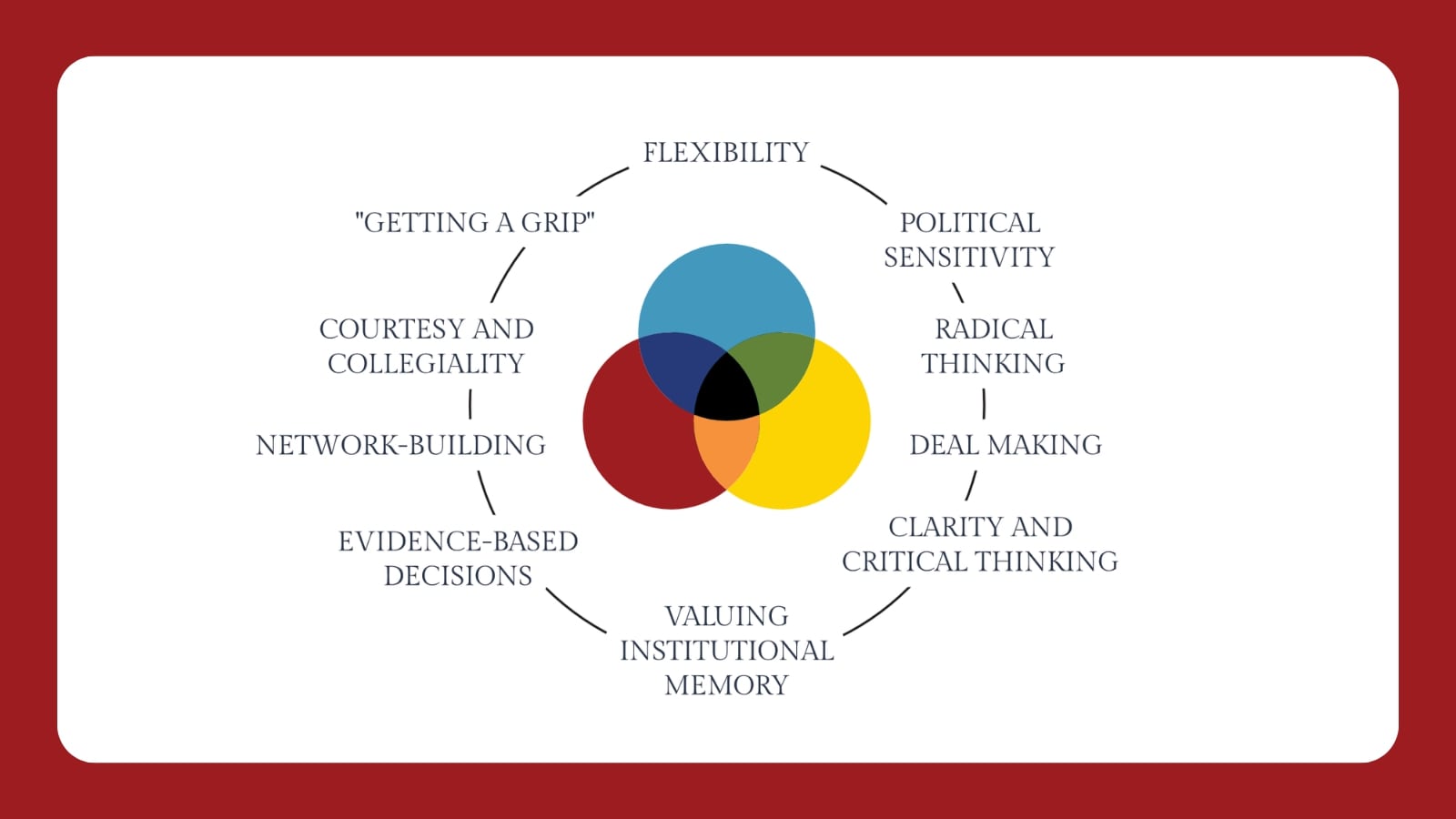

I should start by making clear that Jeremy never claimed to be a “great civil servant”. But he did feel he had learnt a few things during more than thirty years of being a Civil Servant, during which he worked for four different Prime Ministers. The following is a list of his conclusions on the key traits to cultivate in public service, written as far as possible in his own words (with some additional thoughts from some of his contemporaries — civil servants and politicians).

- Flexibility. Being able to change your approach, and how the machinery of government operates. This is particularly critical in the centre, which must adjust more than any other part of the Civil Service when a new government is formed. But adjustments should be made while holding on to some enduring principles — such as avoiding politicisation of the recruitment, promotion and assessment of Civil Servants, especially how they react when decisions are taken, and how willing they are to challenge those in the room. Each government should adhere to these principles, which are codified into processes and rules in the Cabinet Manual, and if they are changed, any alterations should be transparent. Jeremy had to defend these principles several times during his service, sometimes risking his own career to do so.

- Political sensitivity. This is about helping our elected representatives, and their special advisers, get things done because you understand the political context in which they are operating. It means weeding out things that won’t work but always serving up acceptable alternatives. One politician told me that what marked Jeremy out was his understanding of how politicians saw the world, and his recognition that it is they who have to justify their actions to the electorate. Another reminded me of Roy Jenkins’ statement that the essence of a good adviser is to argue for ‘solutions’ not ‘conclusions’, and he thought Jeremy had this quality in abundance.

- Radical thinking, often doing things that have never been done before. This can involve creating structures that encourage such thinking, like the Nudge Unit or Forward Strategy Unit. It also means asking the “unaskable” questions, which are sometimes simple but always practical – such as, why can’t our three military forces work more closely together? But radical thinking should never be radicalism for its own sake. Jeremy drew a distinction between “incremental innovation” (working within the existing legal and policy framework to squeeze out the best possible outcome) and “radical innovation” (where a blue skies approach is adopted and people are encouraged to look at whether the whole framework needs uprooting). He believed that, while both are needed, they can rarely be enacted by the same people.

- Deal making. Jeremy never saw trade offs and compromise – despite the messiness, imperfection and need for granularity – as beneath him. He would bring warring sides together through multiple conversations while inserting new possibilities along the way to create solutions. His method (which took inexhaustible patience!) was to keep asking probing questions until others reached a wise conclusion by themselves. This technique was critical, for example, in the endless reviews that he chaired between the Ministry of Defence, the Treasury and Downing Street. Jeremy hated using power and status to impose decisions, which he argued would only result in temporary compliance, and believed that everyone should leave a negotiation having achieved something with which they could impress their boss.

- Clarity and critical thinking. This means questioning vague terms like “multi-dimensional partnership” – does that just mean holding one big meeting every six weeks, with nothing else changing? His relentless questioning, which perhaps came from Jeremy’s training as an economist, allowed him to get to the heart of problems and meant that – when he needed to – he could dive deep into an issue, while retaining his grasp of the bigger picture. He would question things both in person, and in emails – the latter rarely being more than a few lines long, often just a few words (usually without capitals or punctuation!) but nonetheless with a huge amount compressed into a short space.

- Valuing institutional memory. Although nothing is ever quite the same, the reality is that many things have been tried before. Given this, Jeremy was concerned by the lack of institutional memory within the Civil Service (which is why he allowed me to write his biography). Often big policy issues that flare up in government have been around for generations – welfare reform, local government finance, housing benefit, fiscal rules, social care to name a few. Jeremy built up a lot of knowledge on these topics and – through his network – could access more. This was a huge asset and he always encouraged others not to forget the lessons from history. (He would have been delighted to know that the Chris Martin Foundation, set up in the memory of another great civil servant – and with which the Heywood Quarterly will be collaborating – is aiming to do just this.)

- Evidence-based decisions, combining data with visits to the front line, or as some people would call it, “policy-making by anecdote”. This mix of data and real-world visits created an impetus for change, which is why Jeremy did his regular Friday visits, coming back to his office with armloads of insights and comments to fling around the Civil Service. Connected to this was something he called “opening up” policy – which meant sharing ideas with people outside the Civil Service at an early stage whenever possible. He believed it was far better to do this, and discover failures, than do it later and get “bland, trade association inputs”.

- Network-building. Jeremy created and maintained a wide network of friends, mentees and other contacts. That network was naturally diverse because Jeremy valued loyalty and honesty more than similarity to himself. His view was that everyone was a user of Government, and users often have more useful input than providers.

- Courtesy and collegiality. Even in the face of the most irritating behaviour, Jeremy was invariably civil. As one colleague told me, “I never saw him lose his cool, but I very often saw him lose his patience – an important distinction”. He was tireless in giving positive feedback and encouragement to ideas and to people, and inevitably copied people into messages in skillfully-judged ways to encourage an individual, the individual’s seniors, and others around them to move forward. He had no patience for trivial internal rivalries or chatter.

- “Getting a grip”. This is the key phrase that most colleagues associate with Jeremy and therefore a fitting one with which to conclude the list. His emails reminding people to get a “grip” on a problem were legendary. He would return to issues and the delivery of potential solutions (and blockages) relentlessly over months and years – and expected others to do the same. It is no coincidence that the Delivery Unit, and later the Implementation Unit, was created on his watch. His meetings and “stock takes”, and the culture these created, were built around getting things done. Relentlessness matters more than many realise. Accomplishing things often involves playing a long game, being tenacious, and knowing the moment to return to an issue/argument and make the case again.

——–

While Jeremy possessed all these qualities, a great many other Civil Servants around him exemplified them too. And Jeremy also recognised his weaknesses. For example, he didn’t enjoy – or think he was any good at – giving speeches, and this is one reason why he resisted becoming Head of the Civil Service, though he was eventually persuaded to do so. When he did, many people appreciated his approach, and he prioritised understanding delivery and learnings from the front line. Sometimes leaning into your weaknesses – or finding colleagues who complement you (Gus O’Donnell and Jeremy made a great team) – is as important as knowing your strengths.

Where we can, we will use the new Heywood Quarterly publication to highlight examples of all the traits discussed in this article, whether it is solving an issue by understanding its history, creating a better evidence base, or simply “getting a grip”. I believe Jeremy would be happy with that legacy.