Doug Gurr, newly appointed interim Chair of the UK’s Competition watchdog and Director of the Natural History Museum, warns that the UK is missing out on the fruits of scientific research

Deep in the bowels of the Natural History Museum (NHM) in South Kensington, London, is a vast hidden cavern filled with metal storage cabinets where normally only curators and scientists are allowed to roam.

“Let me show you something”, the Dinosaur scientist said to me as she bent down to pull open an enormous drawer. As it slid smoothly open on its rollers I peered down and there – nestled in a carefully carved-out foam cocoon – was a six-foot-long gently-curved black jawbone with sharp, polished teeth the size of bananas. It was a deadly display of crushing, biting and tearing power.

“This was the first T-Rex bone ever discovered”, she explained. “It’s around 70 million years old and was dug up in 1892 – not long after we opened the museum”.

You don’t forget moments like that.

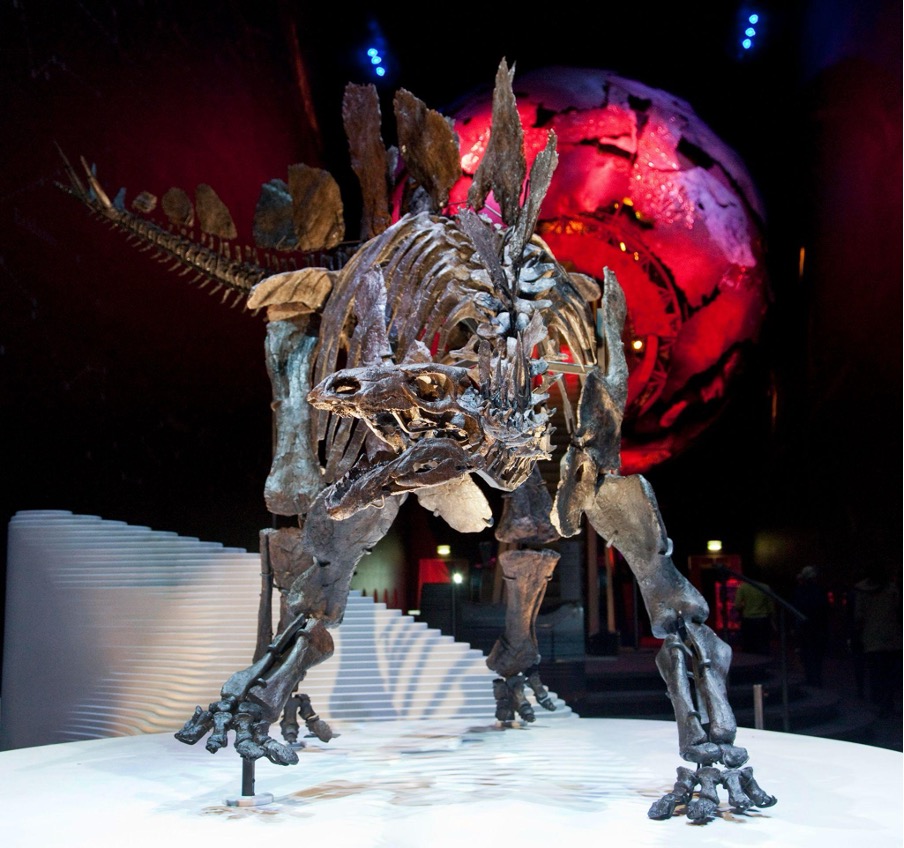

That dinosaur fossil, currently on display in our birds exhibition (did you know that birds are the last surviving dinosaurs?), is remarkable not just for its representation of raw physical strength. Each of the 80 million objects in the NHM collection (that’s 3,000 behind-the-scenes for every one you see on display!) is also a potentially precious source of data. And as our technology develops we are learning more and more about the origins and properties of these specimens. We know where they were found, when and by whom. We have 2D and 3D images. We can classify them into their proper place in the evolutionary tree of life. CT scans, X-ray diffractions, genomic and molecular data add to our store of knowledge. The data becomes our window back in time and helps inform predictions about the future of the natural world.

But for all the excitement about these advances there are two policy elephants (or should we say woolly mammoths?) in the room – the first concerning the issue of privacy and how easy it is to access this public data; the second (and more serious) around the question of who should benefit financially from it. In both cases, as we shall touch on later, a proper public debate is urgently needed.

The Government’s approach to scientific data today stems from an enlightened policy first mooted in 2010 (thanks in no small part to the influence of the then Cabinet Secretary Jeremy Heywood) and set out in the 2012 Open Data White Paper, of encouraging ALBs (arm’s length bodies) and public bodies like the Natural History Museum to make their data freely available to scientists and researchers. As a result of that initiative the data.gov.uk website hosts an astonishing 50,000+ UK public datasets available to anyone who wants to download and use them, usually free of charge and with little or no restriction on use.

At the NHM we have taken full advantage over the last decade by digitising our own collection in pursuit of this hidden value. To date we have digitised some 5.9 million specimens and made the information available – free of charge – to researchers, ecologists, artists, commercial organisations and generally interested citizens all around the world. Those 5.9 million digital specimens might only represent around 7% of the collection but they have already generated more than 46 billion downloads and led directly to more than 3,900 scientific research papers on everything from how pandemics start, how diseases spread, and how changes in environmental conditions affect life here on earth, to how we can genetically engineer heat and drought resistant crops and how close we might be to a sixth mass extinction. In a farsighted move the Secretary of State for the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology (DSIT)announced last year a £155m investment over the coming 10 years to complete the task of digitising all 137 million UK based natural history specimens across 90 different institutions in all four UK nations, including the NHM’s 80 million. This will generate over £2 billion of economic value from the Museum’s collection alone in areas ranging from drug discovery, novel agricultural techniques, gene editing, climate risk alleviation and habitat restoration.

We hear a lot these days, and rightly so, about the importance and excitement around data science and AI. But the raw material of AI is data. Models, computing power, even human ingenuity are relatively commoditised resources. Large scale, well structured, annotated data sets needed to train the models are the truly scarce resource in an AI world. And the UK – as a consequence of numerous prescient historic investment decisions – has some of the world’s most important datasets, many of them sitting quietly in departmental arms length bodies.

Those 137 million digitised specimens will be – by some margin – the world’s largest and most important digital natural history resource. But this is just one small example. In health we have the extraordinary UK Biobank dataset (again by far the largest and most important in the world), the vast gene datasets within Genomics England, and of course, embedded within the NHS, the only truly representative long-term population dataset (linking multiple health indicators) that encompasses primary and secondary healthcare. When it comes to the environment we have the Met Office’s historic weather data, the information collected over decades by the British Antarctic Survey, the marine observation data at the National Oceanographic Centre and so much more. Within culture we have the British Library, the National Museums and Galleries, and the vast archives of the BBC. Within transport with have the TfL transactional data, within education we have the observational data being collected through the National Education Nature Park. All these extraordinary and extraordinarily valuable datasets were largely built through efforts funded by the UK taxpayer.

In a world of AI this data will be the source material that creates enormous economic, scientific and social value. It’s hugely encouraging to see the Government and Civil Service stepping up to embrace the opportunity. Initiatives such as the DSIT mission to create a National Data Library, the Department of Health and Social Care’s embracing of data science and AI as a critical component of NHS reform, the Met Office’s partnership with The Alan Turing Institute to transform weather forecasting, and the ongoing investment in the creation and maintenance of those critical datasets are all to be applauded emphatically. This is one of those areas where the UK can be truly world leading, and has already inspired others to follow suit.

But as indicated earlier, there are two woolly mammoths in the room.

The first is the absence, so far, of a proper debate around what constitutes an appropriate balance between citizens’ reasonable expectations of privacy and the value destruction that comes from an excessively one-dimensional focus on this (albeit critical) issue. We see the challenge most starkly in healthcare. There is a growing acceptance (globally and here in the UK) of the need to move our healthcare systems from late-stage reaction to early-stage prediction and prevention. This will be critical to improving patient outcomes and reducing costs. Yet our researchers consistently complain about the difficulties of accessing the data they need to build and train the models that could lead to this transformation. There were tremendous advances during Covid when the emergency COPI (Control of Patient Information) notices enabled, for the first time, the widespread sharing of primary healthcare data for research purposes. But much of that progress was lost on 30 June 2022 when the notices were allowed to expire with no alternative solution put in place. Some 18 months later we are finally seeing this issue addressed with the Health Secretary’s recent announcements on sharing consented GP data for research – but this is only one of multiple examples of progress being blocked through an absence of clear policies around the appropriate use of public data.

The second – and far larger – woolly mammoth is around the question of payment. It is fairly easy to make a case that these datasets should be freely available for the purposes of scientific research and public benefit – an important part of the UK’s global responsibilities. But is it really fair that this raw material created through investment by the UK taxpayer should fuel vast commercial fortunes that mostly flow overseas to the US, China and elsewhere without any return to the UK?

The global creative community currently takes a very different view as witnessed by the slew of global lawsuits. The UK is rightly encouraging investment in AI innovation and we punch above our weight. But even so, the UK represented only 4% of the top 15 countries’ private investment in AI in 2023 (US investment alone was more than 15 times the UK). Putting it another way, the UK provides a lot of the data (and much of it free of charge) but 24 out of 25 business users are outside the UK. Is our current Open Data approach fit for an AI world?

So if you are a smart official in a central government department what should you do about all of this? Allow me to offer three suggestions. First, please figure out what data you have – both centrally and scattered amongst your sponsor ALBs. Second, do encourage your leaders to think through your department’s approach to digital policy. And third, across government, encourage policymakers to rethink the answer to the question of who benefits from Open Data.

Dr Douglas Gurr is interim Chairman of the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) and Director of the Natural History Museum. He was a global vice-president and head of Amazon UK from 2016 to 2020, and is a former chairman of the British Heart Foundation.